BIBLIOGRAPHY - SARAH BALL

The British artist explains what lies behind the haunting portraits in her new solo show. Words by Chloë Ashby.

Masha looks cold. She’s chalky white with rosy cheeks and a shiny nose. Her lips are gently pressed together, and her eyes are glassy and wet like they’ve been leaking in the wind. She appears not to have any eyebrows, and her eyelashes are barely visible. She stands in front of a black backdrop, wearing a plain navy top and a dull yellow headscarf that’s tied up beneath her chin. Her left nostril is pierced with a tiny gold ring.

Masha’s is one of several faces that Sarah Ball has painted for her first solo show at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London. The British artist, who was born in Yorkshire and now lives in Cornwall, makes seemingly simple portraits that explore the gap between who we are and how we present ourselves to the world.

“It’s something I’ve always been interested in, the manifestation of our identity and the aesthetic choices we make,” says Ball. “I think it began when I was at school. I went to an inner-city comprehensive, and the emphasis wasn’t on education, we were much more interested in music. There was so much happening at the time, in the 1970s, from northern soul to punk to ska to disco, and all those genres came with a look; you could almost describe it as a uniform.”

We’re chatting over Zoom a couple of weeks ahead of her solo exhibition opening. Ball is speaking from her studio in Newlyn, a Cornish fishing town that (together with St Ives) became popular with artists in the late 19th century.

Behind her is another portrait heading to London: a pensive character with a soft black afro, the makings of a moustache, and thread-thin hoop earrings. I inquire about the sitter, and Ball replies, “I found Prudence on Instagram.” Social media is where she sources most of her images. She asks for permission before using them, and occasionally she and the subject end up messaging back and forth. “Some I keep in touch with, and a few I’ve painted more than once.”

After graduating from art school in the 1980s, Ball worked in illustration for almost a decade. In 2005 she completed an MFA and returned to painting full time. “That’s when I became interested in biometrics, the reading of a face and physical features and how they relate to personality,” she says.

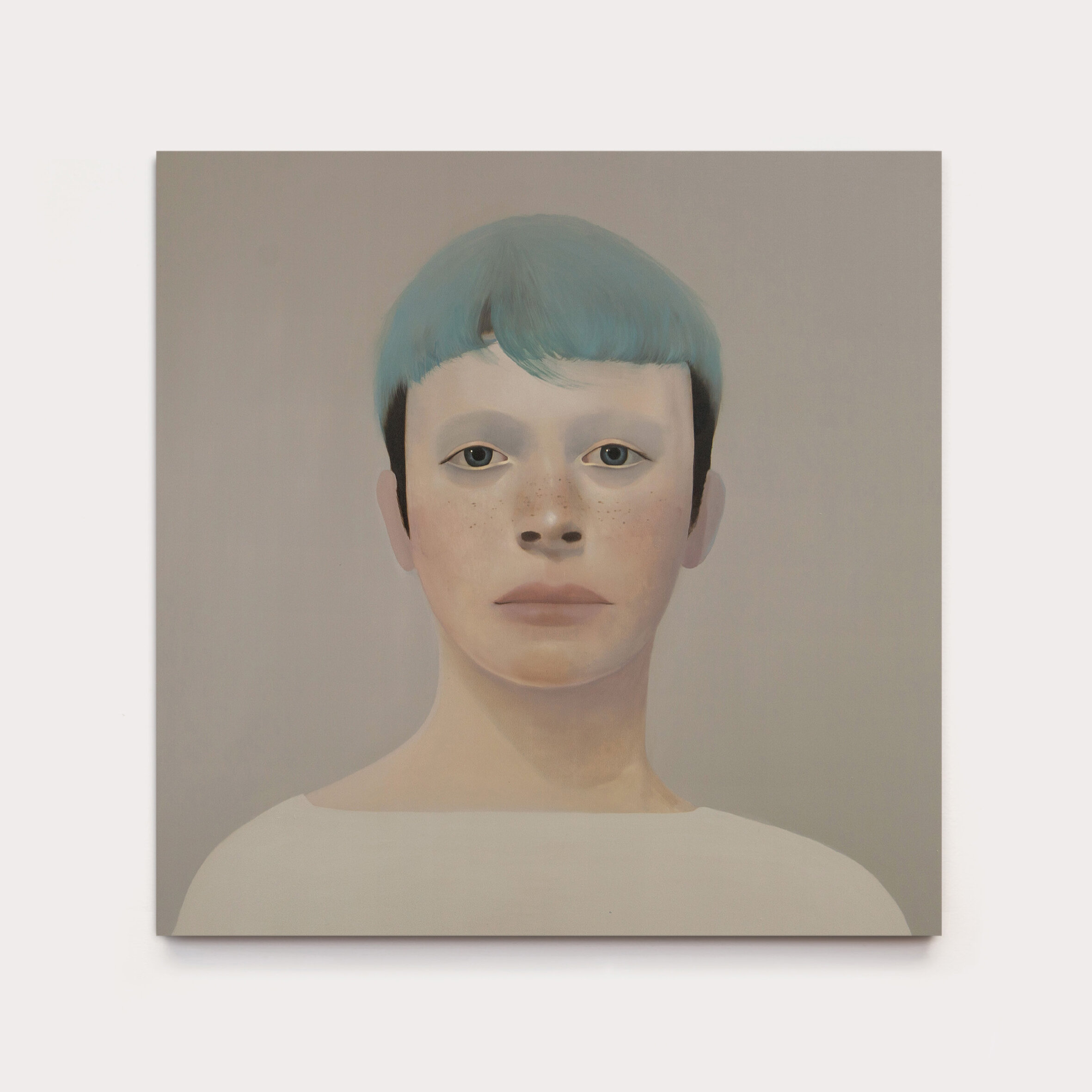

Each of the faces destined for the show defies conventional gender norms. “I’m interested in all aspects of the human condition, including sexuality and gender, which are intrinsic to our identity,” says Ball. With closely cropped compositions and muted backdrops, she zooms in on each sitter and the defining characteristics of their visual identities: a tattoo, a beauty spot, electric blue eyeshadow, a loose ringlet.

“I might be drawn to someone because of the aesthetic choices they’ve made, but it goes beyond that,” explains Ball. “I’m looking for empathy, and I’m looking at the gaze.” Her portraits are as much about capturing a feeling as a likeness. And yet, her style (meticulous, fresh, clear) is unsentimental. There’s emotion, yes, but also an absence. Physiognomy hints at a narrative without ever giving too much away. Pastel colours delicately suffuse each canvas.

“For me, they’re as much about the process of painting as they are about the person,” says Ball, who tends to make two or three portraits at once. This is partly because she wants the paintings to be in conversation with one another, partly (and more practically) because she works with thin washes of oil paint and needs to let each layer dry before adding another.

After she’s found her subject, the act of making takes over. “I’m obsessed with the way the figure can either grow from the ground or sit in stark contrast with it,” she reveals. Ball is constantly striving for balance, which explains why some patches verge on overworked while others remain flat and abstracted.

Ball’s portraits exist in their own time and space. They have a stillness and a luminosity that make me think of Johannes Vermeer’s girls reading and writing letters, pouring milk, making lace. But instead of dazzling domestic scenes, her backdrops are free from distraction. At times they verge on surreal. “I think there’s quite a strong graphic quality to my work, and I’m not afraid of that,” she says. For inspiration beyond the art world Ball looks to album covers and posters, fashion, and filmmakers such as Roy Andersson.

Before we say goodbye, I ask Ball what she hopes to achieve with her portraits. “I don’t have any strong thoughts about how I want people to read them,” she replies. “It’s a purely personal thing for me. It’s all about my process.” Once she’s put down her brushes, she hands over the paintings for us to interpret in whatever way we wish. And therein lies their charm.

Ball is drawn to subjects who shake things up, and her enigmatic portraits encourage us to do the same. “I’m interested in anyone with a strong sense of self,” she says. A sense of self, a point of view, an opinion.

Chloë Ashby, Elephant, 27 January 2022

London — Even if Britain had lifted its Covid-19 international travel ban in time, Sarah Ball would still not have been able to accompany her work to Frieze New York this week.

That’s because in February the British painter — who is also an avid horticulturalist — took a serious tumble while tending to her vegetable garden at home in coastal Cornwall. She broke her ankle so badly that she had to have surgery and was getting around with a wheelchair as she recuperated. For a time she was barely able to make it into her studio, let alone fly across the Atlantic to attend her first solo exhibition at a major art fair.

“I had just managed to finish the work before I broke my ankle, which was amazing timing,” Ms. Ball, 56, said with a soft chuckle during a video interview, adding that she got some help varnishing the works before her surgery. “To be having a solo booth is terrifically exciting; I just wish I could go.”

But it’s a fairly safe bet that this will not be her last opportunity for accolades at an art fair. Though Ms. Ball has been an artist her entire life, international recognition for her intimate and intense portraits has come relatively recently. That’s in part thanks to signing last year with the Stephen Friedman Gallery, which represents prominent artists like Yinka Shonibare, Kehinde Wiley and Lisa Brice.

At Frieze, the gallery will display about a half-dozen works from her ongoing series of portraits that play with themes like sexuality and identity, something she said was partly influenced by growing up during a time when musicians like David Bowie, Chrissie Hynde and Poly Styrene were experimenting with gender self-expression.

Born in Yorkshire, Ms. Ball always wanted to be a painter. But when she was in art school in the 1980s, much of the focus was on the conceptual side of contemporary art. “I was making very figurative paintings, which was very not what was happening in the art world then,” she said.

It was suggested that instead she move more into illustrations and graphics. So for almost a decade she was an illustrator, doing projects for the National Theater as well as a number of book covers. “But,” she said, “I always knew that wasn’t what I wanted to do.”

After having two children — a son and daughter, now both in their 20s — she decided to complete an M.F.A. at Bath Spa University in 2005 and go back full time to painting. “Having children made me realize that I really wanted to pursue my own work,” she said. “This happens in life as you mature; you just question things.”

Her art hints at many inspirations: the stillness of Vermeer, 17th- and 18th-century Flemish artists, and contemporary painters like Lucian Freud and David Hockney.

Ms. Ball said that filmmakers like Terrence Malick and Roy Andersson also motivated her work. “These little vignettes that give you a little bit of information,” she said, “but then invite you to fill in the rest, they sort of ask a lot of the audience.”

That is something many of her admirers say they are drawn to in her works. Michael Taylor, co-founder of the London print gallery Paupers Press, said that the first time he came across her smaller print portraits, he was struck by their surreal and timeless beauty. “You felt there was some narrative behind these faces,” he said, recalling how visitors came to view Ms. Ball’s works at a print fair in New York a few years ago.

“There was something historical, social, political, whatever that belied their simplicity,” he said. “And I found that a very powerful combination.”

Ms. Ball works from photographs — ones she has found on social media, for example — and does not aim to create a “true and utter” likeness. After asking permission, she sometimes exchanges messages with the subject, but she chooses not to meet them. “The idea of having a conversation while I’m working is not for me,” she said.

In 2015, a Cornwall gallery exhibited her portraits of immigrants who passed through Ellis Island in New York Harbor to enter the United States. The word “immigrants,” she wrote, “is weapon, a political pawn, a tabloid headline, to the point that one might forget that we are dealing with human beings.”

Ms. Ball’s works have been exhibited in shows at the Royal Academy of Arts and the Victoria & Albert Museum, both in London, and are part of the permanent collections of the British Museum and Norway’s Kistefos Museum.

“We’ve been inundated with all kinds of requests to see images of the new work, and I am really excited for her,” Mr. Friedman said. “There is a great buzz.”

Owners of her work are also enthusiastic. Beth Rudin DeWoody, a New York-based collector who is on the boards of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, owns six of her paintings.

“When I bought the first work, I had no idea what was going to happen with her career, but I knew she was really talented,” she said, adding that she had a few from the “Immigrants” series. “There’s just something so compelling about them.”

Ginanne Brownell, The New York Times, 4 May 2021

Sarah Ball, Timothy, 2019. Courtesy the artist

British artist Sarah Ball’s strikingly static portraits are uninterrupted too, the backdrops muted, the faces blank. “Things are paired right back,” she says. “I remove objects that tie the subject to a specific time or place, allowing me to reveal the human person in the present.” The result is an absence that leaves room for us to reconsider who we are, or who we might be if we weren’t weighed down by cultural expectations. “I like to think that removing any sense of figurative background or scene creates an emotional space.”

Like Hempton, Ball preserves her sitters’ anonymity. Working with existing and found materials, from historical photographs to social media, she paints portraits that reflect real life—the good and the bad—back at the viewer. “I like the idea of being removed from any relationship with the sitter,” she says. “There’s a distance between myself and the subject and that allows me to expand on the purely figurative.”

Art In Print, Volume 8, Number 6

In the context of the contemporary art work, Sarah Ball has made a number of unfashionable choices: she lives and works in the country (near Penzance in Cornwall); her artworks are usually small; and her subjects are human faces. The faces are those of real people, photographed and archived by various branches of officialdom—mug shots, immigration documents, government-issued IDs.

The format is consistent: a single head, almost always facing the viewer, against a flat background; just enough of the shoulders and chest to give an indication of clothing or accommodate an identifying placard. The smallness of the images is an invitation to intimacy. Ball takes some liberties with her source material—adjusting facial hair or garments, smoothing skin to a marble-like solidity. The result is stylistically modern, streamlined, quietly abstracted. But rather than robbing her subjects of their humanity (in the manner of, say, Philip Pearlstein), Ball’s pictures seem to trim away everything but that Ball’s new polymer etchings with Paupers Press employ the monochromatic nuance of her graphite drawings; only the clothing is given color. The first six are not much larger than snapshots, but packed with interpersonal fascination: there is a middle-aged black woman in pointy glasses; a young, round-faced brunette with bobbed hair; a shock-haired man with the sun-creased skin of a sailor; a bearded bloke who could be a Civil War recruit or a Brooklyn hipster. The last two prints are larger, and the heads—both of young dark-skinned people—fill much more of the image. While the first set of subjects seem bemused, or lost, or resigned, these two stare forward with a slightly stroppy stoicism.

In her paintings, Ball has often used titles that give clues to the subject’s biography (the 2012 painting Conspirator, for example, is clearly Ethel Rosenberg), but these prints are all untitled, as are the related paintings. We don’t know who these people are, or how they ended up in the grip of the system that took their likeness and filed it under “Romanian” or “prostitute,” or whatever. We can make guesses about the time period from accessories like pointy glasses; we can try to intuit character from the tilt of a lip or the droop of an eyelid. But the original institutional photographs were purposefully stripped of passing distractions such as smiles, and of course are looking at an artist’s recasting, not at those photographs themselves, so the forensics are complicated.

Ball entices us into looking, and in that looking to consider the clues and assumptions we use to categorize the people around us, which is to say, to make sense of the world. The slower we look, the more we see, not just in the image, but in ourselves.

Sarah Engledow arrives at the junction of fate and hope in Sarah Ball’s poignant Immigrant series.

Sarah Ball’s recent paintings generally depict people at a fateful juncture - but they do so at a distance. Over years, she’s pored over museum curios, Victorian taxidermy, collected objects and studio and police photography before recasting her sources, ‘creating new characters in imagines scenarios’, she says.

Born in Yorkshire in 1965, Ball has studies and worked in Wales and England; she now lives in Cornwall. Her tiny figurative ‘portraits’ have an unnerving quality of achronicity; it’s hard to tell when they we made. Many of the subjects wear national dress, which changes little over the centuries, but their faces seem old- fashioned, too. Had the people in the portraits been painted from life in their vague own time, we might have expected a different painting style; cubist, perhaps. Right now, it’s hip to be dowdy and expressionless against a grey background. Yet Ball’s subjects seem frumpy without irony; unsettling for the reader of Frankie or Monocle.

The artist based the works on these pages on photographs of immigrants, taken far away and a long time ago. Some are by Augustus F Sherman, a clerk in the US Bureau of Immigration, who between 1905 and 1920 took hundreds of photographs of new arrivals to the USA. In any given week, from his office at Ellis Island, he might have looked out at a queue of burdened men and women in headscarves and hats, big skirts and variously cut jackets. At best, it took them a few hours to be ‘processed’; if a personas physical, mental or moral fitness was in doubt, there were delays. Quite often, evidently, Sherman darted out and photographed people awaiting their fate. Studied in 2018, Sherman’s photographs, like those of his contemporary Lewis Hine, are extraordinarily affecting as records of individuals pulled randomly from a ‘sea’ or ‘stream’ of apprehensive immigrants. Fine is better-known for photographs other than his Ellis Island series, but Ball has treated his photographs of immigrants, too.

Making her paintings of photographs of people, Ball proceeds in the opposite way from a faltering portrait of artist who, having made a sketch or two from life, copies difficult passages from photographs, Ball discards details provided in her source images. In Sherman’s 1910 photograph, the Reverent Joseph Vasilon wears a rigid hat of a Greek Orthodox priest. In ‘recasting’ the named historical man as an anonymous one, Ball has removed bis kalimavkion, made him bald, smoothed his wrinkles, fluffed his beard, softened his eyebrows (several subjects lack brows and lashes; they look more vulnerable without them). In Hine’s photogtraph, the ‘Czech’’ grandmother’ has eyes of ice blue and a minimal slit of a mouth; by these features she’s instantly recognisable in Ball’s painting. The historical woman has a creamier face than her painted equivalent, though, and she wears a striped cardigan. Then again, the artist has favoured her with a countrywoman’s rose cheeks. Ball’s austere palette contrasts with recent colourised images of Sherman’s black and white photographs of immigrants, apparently based on careful research in to traditional costumes of their homelands. Viewable online, they’re strikingly brighter and more varied in colour than Ball’s oils on panel.

The artist delights in details of dress. Yet look closer at the paintings and it’s the variation in their planes and degrees of detail that’s striking. Take the Greek woman. Her coin necklaces and crucifix are really only indicated. Her body’s dead flat, her hair undulates like a piece of card around her high forehead, her head covering’s stiff as crepe paper. The contours of her face however, appear to be moulded from china clay. Framed by her gauzy cap and mound of hair, the Dutch girl’s cheeks are apple-like, from her firm lips kissable, her chin plump. Her dress, meanwhile, is one-dimensional. We start at the vigour of the bright-eyes Romanian Shepherd before registering his cursory ears.

Much has been made of the contemporary relevance of Ball’s Immigrants series. Scrutinising Sherman’s and Hine’s images, we wonder whether the people in them prospered of failed. Another layer of humanity is embedded in Ball’s refined paintings. We sense the tact with which the artist addresses the strangers in the images; from her reclamation and adaptation, we infer care. I’m particularly compelled by an image Ball adapted from a Line photograph: Jew. Her body a sack, her face meek and worried, the woman yet retains a trace of hope for kindness. Is that not the quintessential human hope: that someone will meet the eye, hold the gaze… and move closer?

While it may be a blatantly euphemistic understatement, it’s safe to say that the United States of America, edition 2017, finds itself in “interesting times.” And, as of this writing, nowhere is that more evident than in the interconnected arenas of immigration, migration, and refugee resettlement. So, call it timeliness, call it zeitgeist, or call it prescience on the part of Conduit Gallery and British artist Sarah Ball, but Ball’s just-opened Kindred is a spellbinding, don’t-miss exhibition that speaks volumes about the American experience, actual and mythical, past, present, and possibly future. Featuring 30+ meticulously painted immigrant portraits, as well as a series of drawings, it’s a show for the season; it runs from April 1 through May 13.

Sarah Ball, born in 1965 in South Yorkshire, now living in Cornwall, observes trenchantly, “‘Immigrant’ is a word that has always been loaded with a meaning and weight beyond the dry dictionary definition. The word is a weapon, a political pawn, to the point that one might forget that we are dealing with human beings.” The artist says she’s continually fascinated with themes of identity, and typically works from historical photographs; her previous solo show at Conduit, 2015’s Accused: Part III, was comprised of paintings extrapolated from police mugshots. But this time out, Ball’s focus is on the faces of immigrants, sourced from photographs of new arrivals at Ellis Island in the early 20th century. The photos were shot by amateur photographer Augustus F. Sherman, a registry clerk at Ellis Island from 1892 to 1925. Ball’s paintings, most of them a diminutive 9.5 x 7 inches, are haunting realizations of her subjects addressing the viewer head-on with dignity, equanimity, and a shy curiosity. “I’m always looking around for photographs,” the artist says, “and when I came across these it just felt so relevant, with the words and language and rhetoric that are going around at the moment. It felt like it was just poignant to what’s happening now.” The subjects of the paintings are adults and children alike, and hail from everywhere: India, Russia, France, Lapland, Norway, Holland, and beyond. Augustus Sherman, while a self-taught photographer, nonetheless had an intuitive sense of staging—he posed his subjects against plain walls, and often asked them to don their traditional ethnic costume, their “Sunday best.” Ball says, “I think Sherman just seems to capture something. What’s different to me is the look of the people and how it relates to what’s happening today. There’s no background view in the majority of them, no context really; it makes you concentrate on their clothing or the look on their faces—there’s nothing to detract from that, and that really appeals to me.”

Another key aspect of Ball’s artistic invitation to engage her viewers is the small scale of the paintings. The works have a seductive magnetism that draws audiences into a one-on-one conversation, a dialogue of identities between observer and observed, intimate and universal. It’s a relationship analogous to the notion that if you want someone to really listen to you, try whispering. “For me it feels very natural to work at that scale,” the artist acknowledges, “although I am beginning to experiment with some larger pieces. A lot of times the subjects I’m drawn to are very quiet images—the draw for me is that they are often a very quiet thing, and it just feels (like) the most natural scale. And I also love the fact that you have to go in—you have to step in to the painting to really see it.”

Close inspection of the oil-on-board paintings reveals another astonishing piece of Ball’s aesthetic: the surfaces are immaculately brushstroke-free, her subjects seemingly emerging from a world away, as if conjured through some arcane alchemy. Her technique involves gesso prepping of the board, building up multiple thin layers of paint with very small brush strokes, sanding between the layers, and a varnish topcoat for a cohesive finish. The portraits speak eloquently of her technical mastery. Small wonder Ball was named Welsh Artist of the Year in 2013, among many other accolades.

“We’re living through a period of mass immigration now,” the artist adds, “and the immigrants in the 1900s were met with just as much fear and xenophobia. They were considered to be backwards and they were examined for illiteracy, whether they were criminals, or whether they had money…I just feel that things have slightly moved on. I’m pretty sure that Brexit only happened because people played that immigration card to the point that they started believing it and became very fearful of something. So it feels like it hasn’t changed, in a way.” As ever, Lady Liberty and Emma Lazarus have the last word: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…” The time is now—encounter your Kindred at Conduit Gallery.